Roseburg Forest Products’ journey to success

8 April 2011The aim of Jon McAmis, Roseburg Forest Product’s (RFP) director of human resources and corporate LEAN champion, is that eventually it will be simply thought of as “the way we do business – as natural an activity as filling out a time card or observing safety regulations”.

What he is referring to is the journey RFP has embarked on with LEAN manufacturing; a journey it began in July 2009 when 10 staff began a course of study dubbed LEAN University. Ten months later, after each had completed 300-plus hours of training, they set about implementing their new-found knowledge.

“It was very much project-oriented learning. Learn one day and go do the next,said Mr McAmis, explaining that he and his LEAN colleagues applied their training on an almost daily basis at RFP’s Riddle Plywood mill.

That initial group of LEAN University graduates has been followed by a second, with a third class due to graduate later this year. To date, various levels of LEAN training have been undertaken at all four RFP plywood mills – and at its engineered wood plant. Implementation is in its infancy at the company’s sawmill.

Blend of education and passion

Mr McAmis spoke frankly of the challenges of implementing LEAN once employees were informed.

“The response was as expected. Many had seen initiatives come and go and some stated that ‘this, too, shall pass’. There was denial, confusion, rejection. But, once training got underway and the framework for the implementation of LEAN was established, our employees began embracing it with a passion. I can now safely say that we are very close to reaching critical mass as far as acceptance of LEAN is concerned.”

Mr McAmis believes that the passion for LEAN comes from its principle of employee engagement and that, because of this, employees now readily take ownership in the performance of their ‘mini-businesses’ – the areas of operation in which they work and for which they are responsible.

“We’re seeing employees who never raised their hand at a meeting doing so now because they know their input is important, and expected, under LEAN,he said.

According to Mr McAmis, LEAN has well-defined guidelines, which are transferrable across industries and disciplines. LEAN focuses on the principle of continuous improvement through the relentless elimination of waste, the setting of strict operating standards and the engaging of staff in the process.

“It has to be a holistic approach in which we engage not only employees’ backs and hands, but their hearts and minds as well,he said, adding that making the proper tools available is rudimentary to the process. One such tool is the five S’s.

“A place for everything and everything in its place. Sound familiar?he said, citing the example of his own home workshop in which he has utilised the five S’s:

1. Sort – decluttering improves productivity, improves housekeeping, instills pride;

2. Shine – painting, degreasing, cleaning makes machinery perform better;

3. Set – making sure that everything is in its proper place improves efficiency;

4. Standardise – establishing and communicating new standards;

5. Sustain – auditing and improving the process.

“The aim is to achieve level loading and reduced lead time. To do so you must examine every minute aspect of production, eliminating everything from the process that is wasteful and non-productive. Reducing lead time ensures you get paid sooner, which is the desired outcome of all businesses,said Mr McAmis.

An equally important aspect of LEAN is the identification and elimination of waste, of which Mr McAmis identifies eight main culprits.

1. Defects – impacts reputation, don’t get paid for defects, reduces profits;

2. Overproduction – inventory costs money, wastes energy, inventory prone to damage;

3. Waiting – non-productive downtime (man and machine);

4. Non-value-adding – over-processing for which the customer won’t pay;

5. Transportation– time wasted in moving inventory, double-handling;

6. Inventory – money tied up in stock;

7. Motion – inefficient movement of workers;

8. Employees – the untapped abilities and skills of staff.

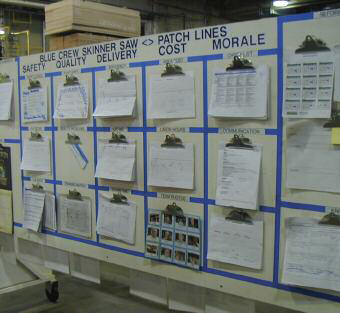

According to Mr McAmis, the recognition of employees’ efforts constitutes a major part of the LEAN process. Each day, each ‘mini-business’ posts the results of its day’s labour on ‘glass walls’, so named because of the transparent nature of the data posted on them.

“Those glass walls make results available to everyone and results are displayed in such a manner that it is easy to follow,said Mr McAmis. “The data is directly correlated to satisfying the key metrics of LEAN – quality, cost, productivity, safety and morale, and because each of these key metrics can be both qualified and quantified, trends can be easily prepared and progress followed.”

At RFP’s Riddle operations, LEAN manufacturing manager, John Whiteley, spoke of LEAN in glowing terms. “LEAN,he stated emphatically, “works!”

Said Mr Whiteley: “Kaizen is a Japanese expression that is fundamental to the principles of LEAN. It means continuous improvement on an incremental basis and it is the means by which we are able to identify problems as being opportunities for change. One way this principle is applied is with a Kaizen or rapid improvement event”.

Kaizen events have a huge impact

He described Kaizen as a blitz on a production centre, the objective of which is to attain rapid and intense change for the better and to maintain the positive results achieved through proper maintenance and adherence to the principles of standardisation established by the event. Once a standard is established it remains inviolate, unless it can be further improved. In other words, the problem must be cured, not simply have a Band-Aid applied.

Mr Whiteley described a Kaizen event as taking anything up to 12 weeks to complete, depending on the complexity of the equipment, and requiring the input of up to 12 team members. An action plan is devised and followed until success is achieved.

The approach to such an undertaking prior to the implementation of LEAN would have been haphazard and ill-reported, with little opportunity for follow-up, according to Mr Whiteley.

“We’ve had really excellent results from our Kaizen events to date. In the case of our dryers we’ve seen a productivity increase of 27% and we’ve realised significant first-pass yield on our robot pluggers. There have been many other areas of improvement as well, such as a 50% time saving in small-batch turnover time. In fact, all our key metrics have improved. The glass walls tell the story. LEAN really works. Our top executives know it. Management knows it. And the people on the mill floor know it, too.”

“The biggest improvements have come from the process itself, not from the implementation of new technology but from the better utilisation of existing technology,concluded John Whiteley.

![?Many of the principles [of LEAN] are intuitive, with the structure a balance between protocols and entrepreneurship, with some art thrown in.? John Whiteley, LEAN champion, Riddle Plywood](/Uploads/images/files/Apr_May_2011/Roseburg_Forest_2.jpg)