In the right direction

17 November 2014Mexico’s wood panel industry appears to be on the verge of a slow motion revolution as the sector is poised to resolve some long-standing key issues that have left it trailing its South American counterparts, says Richard Higgs in the first of his reports from Mexico.

For years, Mexico's national panel makers have struggled to break out of a seemingly endless cycle, dictated by the country's traditional dependence on plywood, its dire lack of a sustainable wood fibre resource, and an almost total reliance on imported MDF.

Then, seven years ago, just as panel production seemed to peak on the back of a buoyant economy, the industry, along with Mexico's furniture sector, suffered a further body blow as both were engulfed by the 2008 global recession.

In the crisis years to 2010, panel markets declined dramatically and plant utilisation was hit hard. Since 2007, almost 120,000 jobs have been lost in Mexico's furniture sector and the wood panel and other related industries.

"It's been very tough for the whole industry in the past six or seven years," recalled Leo Schlesinger, newly-elected president of the Mexican wood panel producers association ANAFATA.

Even so, he added, the crisis forced the industry "to focus on what is really added value". That led to panel manufacturers streamlining their operations, taking out costs and becoming more competitive. As a result, much of the industry emerged from the recession leaner and stronger than before.

There followed a new period of consolidation in the sector with Masisa México, part of the Chilean Masisa Group, assuming industry leadership through its US$54.2m acquisition last year of the country's dominant player, Mexican particleboard producer Rexcel.

At a stroke, Masisa more than tripled its particleboard capacity, to 600,000m3 per year, acquiring three more plants with extra board finishing and resin manufacturing facilities across the country. The deal provided valuable synergies and gave the Masisa group a competitive production base in Mexico.

This move by the Chilean giant, a regional sector leader with operations across South America, raised speculation it was reacting to acquisitions made in and outside Latin America by rivals, including fellow Chilean group Arauco.

However, its initiative was welcomed by other Mexican producers who feel consolidation has helped to steady the Mexican market. "It was a smart move by Masisa.....you have a stronger competitor, but the market itself is more stable. I think that was good for the competition," commented Emilio Ayub, chief executive of another leading Mexican producer, Duraplay de Parral.

The Masisa initiative helped set the scene for the industry's single most groundbreaking development to date: plans to construct Mexico's first world-scale MDF plant. However, as with the old adage about London buses, you wait an age for one fibreboard mill and then three arrive at the same time - by 2016!

No sooner had Masisa México revealed it would erect a 200,000m3/year MDF line at its Durango site in central Mexico than plywood and particleboard maker Duraplay, based in the US border state of Chihuahua, had announced its project for a similar-sized line.

Days later, a surprise third plan for a 200,000m3/year MDF line, more than a thousand kilometres south in Tabasco state, was promptly unveiled by an industry newcomer, teak hardwood specialist Proteak group. This line, since increased to 280,000m3 per year capacity, will be fed by the firm's local eucalyptus plantations.

Change is in the air. Fresh competition in Mexico's growing MDF market should gradually staunch the overflow of costlier fibreboard imports from South America - especially Brazil - and from the US. Domestic supply should also provide a cost-effective substitute for plywood in the national furniture industry.

"Plywood is a big factor in the industry. It determines the price of MDF; and MDF the price of particleboard.....MDF is the perfect transition material for a traditional carpenter - even with the use of their own tools - not particleboard," pointed out Leo Schlesinger, also the Masisa México CEO.

Up to now, with import domination and a lack of competitive fibreboard in the market, there has been neither incentive, nor the economics, to replace plywood with MDF locally. So the traditional cycle continued, Mr Schlesinger explained.

The Mexican cycle is also perpetuated by a lingering perception among local carpenters and furniture manufacturers that particleboard is an inferior product, dating back to the poorer quality of early panels against plywood and solid wood, Mr Schlesinger told WBPI in June.

The Masisa boss is confident that when the new MDF plants are up and running, domestic output, now barely 100,000m3 per year from Mexico's small producers Macosa in Mexico City and Emman de Ocotlan of Guadalajara, will cut away at least 50% of the current import total.

Masisa and the other firms behind the latest MDF projects now see a "huge opportunity". In a country of 120 million people, with per capita consumption [of MDF] a quarter to a fifth of that in South America, and one seventh of what it is in Europe, "you can only see the upside," according to Mr Schlesinger.

Even so, there is still the major question of Mexico's desperate shortage of a sustainable forest fibre. The country remains almost entirely dependent on its dwindling native forest resource, which is tightly controlled and preserved through the country's traditional 'ejido' community landholding system.

"We would have invested in a plant with twice as big a capacity if we had assurances in terms of the fibre [available]," admitted the Masisa chief executive. He stressed that it has taken his company a decade to develop its consistent fibre supply in the three states where it now has plants.

"If you were to compare the forest industry - the legislation, resources, the know-how and the implementation - in Mexico with what you find in Chile, Brazil or Argentina, we are miles away [from them]," admitted the Mexican panel industry leader.

He stressed that his industry is trying to "implement the right policies" to change from native forest wood supply "to a plantation-driven resource, which changes the game completely".

But, he warned, this will take time and the planned MDF plants will not reap the benefit immediately from any change. "Even if we were successful, it's going to take another 20 years for this to have any impact on our industry," Mr Schlesinger conceded.

Back in 2007, Mexico's panel makers were edging towards forestry reform, although they recognised any change would come about long-term. They acknowledged the attraction of developing tree plantations in southeastern Mexico, with the region's high-yield growth rates.

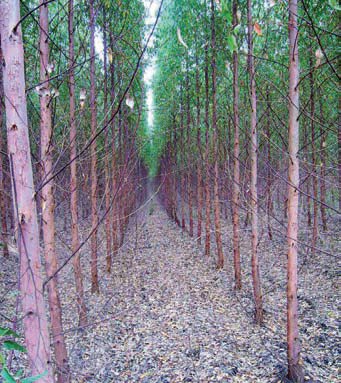

In fact, eucalyptus planted there by an offshoot of former player Rexcel now forms the fibre base for the MDF plant in Tabasco state being built by the forestry firm Proteak.

However, since then, widespread plantation for industrial use failed to take off and the hoped-for wood basket did not finally materialise. Panel industry leaders still point out that it is not economical to ship wood more than 1,000km to their present industrial base in northern and central Mexico.

Nevertheless, Proteak could now 'break the fibre mould' with its bold MDF scheme, financial backing and forestry know-how. It has plans to double the eucalyptus productivity in five years and achieve yields of up to 60m3/year/hectare.

Other planting initiatives, including one in central Mexico to grow the pine base, are being backed by Masisa México in Durango state, with plans for 10,000ha of third party plantations by 2018.

But so far, these are modest plans. Industry lobbying has made some impression on the Mexican government and producers are now able to exploit smaller diameter pine trees previously not cut down, thanks to government incentives and changes to the 'ejido' har vesting programme, according to Duraplay's Emilio Ayub.

But panel producers acknowledge that they are up against a traditional government mind-set based on protecting Mexico's forest assets, rather than exploiting them in a sustainable way.

In Mexico, overall wood production has plunged in the past 14 years from 10 million m3 to less than six million m 3 and commercial forest plantation scarcely amounts to 250,000ha - 80% of it small plots - after 15 years. In contrast, Ur uguay now has one million hectares planted in just 10 years, points out ANAFATA's long serving director, Armando Santiago.

The association is targeting the industry's structural issues such as the lack of wood supply. "We are working as an industry body by engaging the authorities and the different actors [to get] a more sustainable forestry supply. That means [fi nding] ways to incentivise the plantations in Mexico," said the ANAFATA president.

Government response has been "positive" and it understands the potential and the issues, "but whether that translates into policies remains to be seen", said Mr Schlesinger, who believes that the panel industry is now moving in the right direction.