Plywood at the V & A

13 October 2017London’s Victoria & Albert museum is staging an exhibition about plywood and the contribution that it has made to design and modern living. Julian Champkin visited

It is not often that this magazine reviews exhibitions at one of the world’s major design museums. In fact this may be the first time it has happened. But when London’s Victoria & Albert Museum puts on a special exhibition entitled “Plywood – a Material story” it clearly enters well within our remit, and visiting it becomes a duty as well as a pleasure.

It is not a particularly large exhibition – it fills one hall, by the entrance – and is aimed, of course, at the non-specialist; but even those in the wood based panels industry will learn something – and will enjoy it.

It is far from being entirely design-led. Visitors will depart knowing how plywood is made – it has videos of veneering lathes, ancient and modern, in action, and a brief section on CDC. The history of plywood is covered, from ancient Egypt through 18thcentury chair-backs made of layers of veneer laboriously built up by hand; it shows early and modern and attempted applications, from the Jules Verne-like cylindrical hulls of pneumatically-propelled Victorian train carriages exhibited at a New York industrial fair in 1867 through aeroplanes, boats and automobiles to sewing-machines, tea-chests and prefabricated housing.

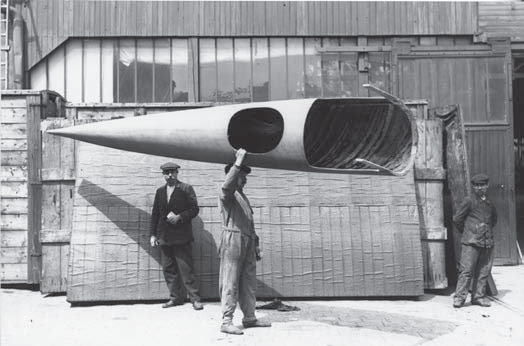

It is well-known, for example, that the fuselage of the World War Two Mosquito fighter-bomber was made of plywood. They have one in the exhibition, hanging from the ceiling, with film of how it was made – by hand-applying veneers to a concrete former and strapping them in place with metal bands until the glue dried. The work was done by women, their men-folk being at the war. What is less known is that the technique was first used for aircraft as early as 1912. A photograph shows a workman, singlehanded, carrying the monocoque fuselage of a French Deperdussin aeroplane, a type which set the world speed record in that year.

Happily, the plywood to construct the exhibition itself was donated by James Latham, the timber company which, in the course of its 250-year history, during the war also supplied plywood to build aeroplanes.

The subtitle of the exhibition is “Material of the Modern World.” Racing cars are here; so is prefabricated housing; so too are exotics such as copper-faced plywood from Estonia, – manufactured as a material for doors in 1933 – and a book written and printed in Antarctica by Sir Ernest Shackleton’s expedition of 1907-9 and bound in plywood from one of the 2,500 packing cases that withstood polar blizzards and being buried in ice, all without harm to their contents.

Synthetic glues from the 1930s made the material water-proof and increased its utility. “A once discredited material now saves vital aluminium, offers new hope for mass production and yields faster manufacturing” wrote Fortune magazine in 1942, celebrating its role in the American war-time economy. It was hailed back then as the material of the future. The same description could be used today.

The exhibition is valuable. The wood based panels industry needs public awareness of why engineered wood is so important to the world. The exhibition does not preach, but visitors from outside our industry will leave with a better awareness of the role that wood plays in the world that we live in.

If you cannot visit the exhibition before it closes, fear not. The book that accompanies it, by Christopher Wilk, Keeper of Furniture, Fashion and Design at the V & A, will remain available. It is large and comprehensive, covers far more than the exhibition can, and is excellently written and beautifully illustrated. You will find no better history of plywood or record of the useful, sometimes beautiful, sometimes astonishing things that can be done with it. For the latter, I would point you to the photograph on page 93, taken in 1929, of a group of girls at the beach wearing plywood bathing costumes. More things are made from plywood than this world dreams of.

Leaving that aberration aside, the book would make an excellent Christmas present for anyone connected with the industry, or for their family.

When your children ask “Daddy (or Mummy), what do you do all day?” you can show them the book. And if they read it before you do, they may surprise you with things they know about plywood that you do not.