Kingfisher fights for protection

30 March 2018Recycled wood puts greater strain on equipment and machinery. Kingfisher Industrial, manufacturers of wear resistant process plant and equipment, identified this problem back in 1990. Julian Champkin spoke with MD John Connolly.

As pressure grows on sources, and prices, of virgin wood, recycled wood is increasingly important to panel makers. But recycled wood brings problems. In particular, the inevitable contaminants that it contains abrade machinery and can greatly increase its rate of wearing out. Costs of replacement or repair can be huge.

Since the wood based industry has moved from utilising virgin wood to recycled wood as a raw material the effects on key operational process plant and equipment have been immense.

In any wood panel process you have large volumes of material flowing as particles, or being moved mechanically, and at high velocities. Wood fibres on their own are not particularly abrasive – but the combinations of wood and contaminants that are being handled now are much more so. Secondhand material brings problems due to ferrous metals, glass and silicates it contains. All of these are abrasive materials and hugely increase levels of wear.

Contaminated raw material must be chipped, cleaned, dried, mixed, pressed, and then stored. In every one of those processes the raw material comes into contact with machinery or piping or containing walls. It does so in large quantities, at high velocities, and repeatedly, in fact constantly, impacting the surfaces and abrading them. And of course the contaminants, those fragments of iron and glass and the rest, abrade far more quickly and viciously than does virgin wood.

One UK company spotted this early and has provided a number of solutions for large PB, OSB and MDF manufacturers. We spoke to John Connolly, managing director of Kingfisher Industrial.

“In effect we offer a complete service,” he says, “from consultancy to manufacture and installation. Protection is our unique selling point.” And he explains why and how that selling point came about.

“If you refer to the larger operational equipment manufacturers, they will most frequently offer a one year warranty on all capital equipment supplied to the end user. This will be in line with customer’s budget terms. Panel manufacturers then expect to see this equipment last significantly longer.

After the 12 months is up ownership is passed onto plant and engineer managers who inherit the responsibility of keeping the plant running as efficiently as possible, meeting annual production output goals.

"But very rarely will equipment last longer than 12 months. Once it starts to wear away steel structures perforate, and material begins to leak through. Plant managers look for solutions on how they can prevent production from stopping.

"Many customers will revert back to the original manufacturer and ask them for a replacement. Undoubtedly the plant will be up and running again, but at what costs, for how long, and what return on investment have they achieved against the loss of production?”

John points out a better solution. “Alternatively, manufacturers have the option to approach us. We can offer them equipment with an added inner wear and abrasion protection barrier, which will help increase the service longevity of the equipment by up to 3-4 times or even longer, depending on the operating parameters.

“Problems of wear have become particularly acute in recent years in the wood based panels industry. Panel makers are at the bottom of the receiving chain. They come after the wood-burning power generators, who get premium investment, subsidies, and grants and so on as long as they are using a renewable source of raw materials. So the wood industry is picking up the pieces: the quality of its source of supply is going down.

“So there is an ever-growing demand for re-used and secondhand wood – and it is a seller’s market. Hence many global wood product manufacturers have set up their own recycling centres. The downside even there is that the quality of product coming in through the door isn’t what it was long ago when they used only virgin wood.

"And the problem is getting worse: because electricity is expensive, panel companies now are installing their own Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plants, and use their own refuse wood to power their manufacturing plant. This is wood that has already been rejected as far too contaminated to make panels, so it contains even more impurities than the rest. This adds additional wear-and-tear issues to the power-generating part of their operations as well

“Seven years ago was the tipping point when this became generally realised. Back then we began offering a ten-year guarantee that was unique. Individuals began to realise that if they don’t invest in wear protection at the outset they won’t get 12 months use out of their new equipment, let alone 14 months.

"So what do we do? There has been a significant change in the technology over the past 10 years. What gave a level of adequacy back then does not do so now. There are new materials, there are enhancements to old ones."From the primary end of the process such as the sorting line all the way to the end of the press, every piece of equipment in between those two will suffer abrasion and will now have some level of protection built into it. Even past the pressing lines there are contaminants in the panels, which wear out the sanding belts faster. So we get involved in everything from debarking to sorting lines and everything in between.

“We visit, consult, and offer a guarantee of performance. If we are successful the customer buys into our offering and we go through design and consultation stages to work out what changes are needed in the manufacturing and installation to give more protection to capital investment.

“It is more than return on capital. It is return on on-going expenses as well, because it allows the maintenance engineer to concentrate on his main job instead of firefighting to find ways of keeping worn-out machinery running.”

It comes down, says John, to questions of philosophy. “It is the equivalent of a car tyre lasting 15,000 miles or 100,000 miles. You pay more for the better tyre, but only three times more, not six or seven times more. So in the long run you save money (and disruption, which is also money). If you are that way inclined as an engineer that is what you would choose – but not everyone is!

“There is always a trade-off. The technology we bring to the table protects. We offer the additional services or products, and you don’t need the bells and whistles if you are taking the short view. And of course if your site is winding down then you might legitimately think only of the short term. It depends on the curve and the mindset of the engineers and the company.

But if you don’t pay for these things at the outset you will be paying more in the long run. We find that most engineers are benefitting. Otherwise they find themselves with a never-ending task like painting the Forth Bridge. As soon as they fix one wornout component another one goes. We take that worry away.”

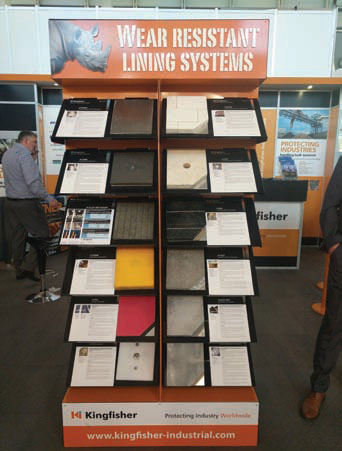

How do they do it? Protective surfaces come in three basic types – ceramic, metallics, and polymers.

“We are unique because we use all three,” says Mr Connolly. “Some we manufacture ourselves, and we have relationships with other manufacturers who make their products for us. So we approach things in a different way to a company that just makes one thing.”

Metallics, in particular hardened steels, are the familiar protective materials. The synergy between the mechanical engineering doctrine that engineers and plant managers have studied during their careers and the benefits of hard steels has engendered many of its applications in industry today.

In other words it is the default, no-thought choice. As with most materials, technology is creating new processes to hone its characteristics. Improved quenching and tempering methods for hardened steels, and blending minerals to achieve superior cast alloys, have improved performance substantially. Materials such as QT plate, work-hardened, ferritic and martensitic alloys and chromium and tungsten carbide plate are now standard.

Using soft polymers against wear appears counterintuitive, but materials like rubber absorb shocks of impact so do not transfer the compressive forces to the surface beneath. Polyethylene with its very low coefficient of friction allows materials to glide over it without scouring the surface. Polymers, in sheet form, cast, or applied as a spray, can combine these qualities to give resistance against wear from both mechanically and hydraulically conveyed materials. But it is only in the right application that polymers will give a significant payback compared to more traditional types of protection.

Ceramic lining is classed as a new product. Despite proven success, there is still doubt in some minds whether ceramics can significantly outperform steel. But the material continues to increase its market share year on year and many industries are now benefiting from investment in ceramic technology.

What does seem indisputable is that no one solution fits all. Combined Heat and Power plants require different ranges of ceramics and metallics that protect them and that work up to 1200°C. “We have experience of what works - and of what doesn’t,” says Mr Connolly. “Some of that experience was costly, but we know now what works in what environment. We know what contamination in the wood stream does up and down the production line.

“We can fit our linings to new equipment. Refurbishment is an option as well. For example when processing wood panels most companies mix the primary source with resins. The mixer tends to be horizontal, with shafts that are rotating at high speeds. So you get friction, heat and wear. Sometimes they wear out in months, sometimes in years.

"A number of UK and overseas companies use our systems. They used to replace their mixers every 12 to 18 months. Now they replace them every 14 years.

“Of course it is not just the machines that cost money. The times spent out of commission also cost. If a machine is not turning it is not earning. In other words when nothing is coming out from the far end of the production line, the company is making no money.

“And replacing a machine involves not just the cost of the hardware, but also of the associated equipment to effect the replacement – the scaffolds, the cranes, the manpower. You can add in the health and safety issues – you may be asking your installers to work in confined spaces, at heights, in hot temperatures.

“And as ever, there are environmental issues. It is when the product comes out of the side of the casing that you know you have a major problem!

"Plant managers then get faced with a cycle of issues. They have to stop the plant to repair it, control the contamination, sort out legislation and maybe fines, and unless you are in the middle of nowhere there will be 200 telephones ringing at once demanding to know what is happening… It is the nightmare scenario for any company. All our clients are big international companies. They take these things seriously.

“As a company we have been established for 30 years. We employ 50 people and have managed turnovers of more than £6m a year. I believe we were pioneers. Others have followed us. When you are the first you benefit a lot and lose a lot. When you are second you see where the losses were made.

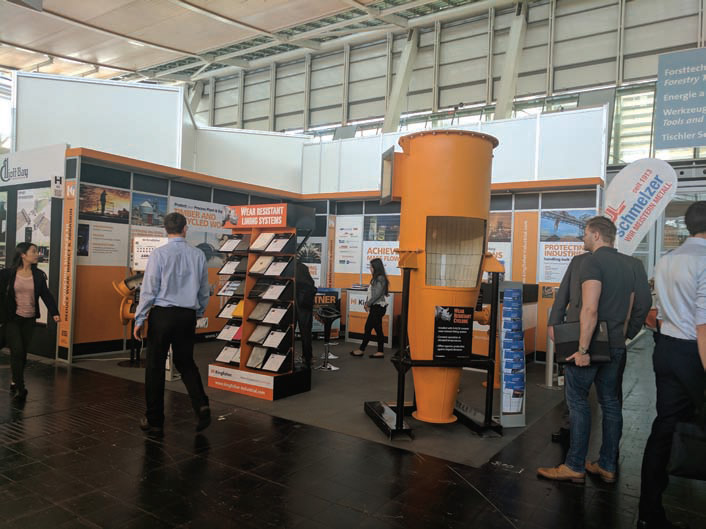

"We are UK based; we have contracts in Romania, Turkey, Belarus. Since Ligna last year expressions of interest have been booming. We have recently received an order from a particleboard manufacturer in South Korea who has been active in the wood processing industry since 1961.

"The main engineering personnel visited us last year during Ligna and expressed interest in the range of wear resistant lined equipment we had on display such as our Cyclone, Diverter Pots and Pipework systems. Speaking with the engineer they explained that they are battling against the use of highly abrasive contaminated wood lumber and are having to replace equipment time and time again.

"Before us, everyone used a derivative of steel armour plating as the industry standard, which is fine to use in standard applications, but not in arduous ones. We have a ten-fold performance increase over it now.” Which is a situation he sees as set to continue. “ In all industries, production levels have increased while manning levels have decreased. This puts huge pressure on managers, who only have so many hours in a day; so they in turn expect more from their supply base."

Recent events in the UK reinforce his optimism. “The next 10 to 20 years will need investment in highways, in nuclear energy, in affordable housebuilding: constructionrelated products will be critical. It is a western European problem also.

"Raw materials to meet the demand will be in short supply, there is a need for processes to be far more efficient than they are now. Which means that equipment must operate longer, harder, without downtimes.

“Which also means that industry will demand reliability and machines that are protected from wear. Which means in turn that Kingfisher will be needed. And we are still knocking on doors!”