A challenging, everchanging, business

7 February 2019In recent decades, the pacific northwest's plywood industry has declined, with survivors diversifying into a variety of veneer-based products. Can the industry continue to stay ahead of evolving markets? Richard F (Dick) Baldwin, PhD and Richard W (Rich) Baldwin, MBA try to answer that question

The Pacific northwest plywood industry continues to endure an unprecedented era of turbulence, which began in the 1980s. The concurrent trends of OSB becoming a lower-cost substitute for plywood, and timber shortages caused by environmental concerns, prompted the crisis.

The business cycle and secular shifts ended in the 'Great Recession' (December 2007-9).

West coast plywood production decreased from 9.6 million m3 in 1990 to about 6.2 million m3 in 2011, as mills closed or downsized. The slow recovery which followed that global recession has been dampened by increasing plywood imports from Asia and South America.

However, some plywood operators survived and now prosper. These ‘survivors of the survivors’ have demonstrated the ability to innovate through decades of perpetual crisis.

Which mills continue to operate? What major events and decisions impacted survival? What are now the strategies of the survivors? This historical analysis provides important lessons for operators in the Pacific northwest – and elsewhere.

An industry in retrospect

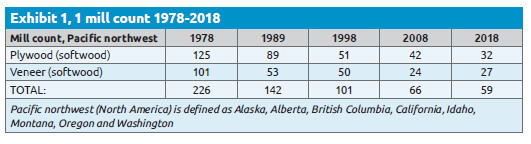

In 1978, just before the commercial roll-out of what became plywood’s competitive nemesis, OSB, the Pacific northwest plywood mill count totalled 125.

OSB uses plywood’s core concept of cross-layering fibre to enhance structural properties, but with cheaper log flakes, rather than peeled veneer. The expansion of the OSB industry hastened the decline of the Pacific northwest plywood industry to 89 plants in 1988 and then 51 a decade later (Exhibit 1). “…[OSB] is the smart man’s plywood,” declared Harry Merlo, then ceo of Louisiana Pacific and the most visible promoter of OSB: OSB marketing promotions were built on that theme in the 1980s.

Owners of large integrated forest products corporations decided that they could earn higher returns on investment than with commodity plywood production through building OSB plants, investing in high-tech sawmills, or just selling raw logs. Andy Sigler, ceo of Champion International, asserted during a 1985 meeting that: “plywood is really a lousy business”.

These colourful comments by two respected leaders reflected the common wisdom that plywood had a dismal future. Mill after mill was suspended or sold.

Reconfiguring the industry

Inflexible big-company business practices, combined with rigid work rules of organised labour, failed to provide the capital and operating flexibility needed for survival: Initiative was stifled, innovation was feared, and financial returns fell. Corporate decision makers forgot the resourcefulness and innovation which were core legacies of Pacific northwest plywood pioneers.

As the OSB industry developed, commodity plywood producers chased fewer orders. Consequently, large corporations sold, or closed, dozens of unprofitable mills.

Entrepreneurs purchased the best of these assets and reconfigured the mills to better align capacity with market demand. These survivors were motivated by the considerations of ‘Find a market and serve it; find a log and peel it’.

It was not uncommon to have integrated plywood mills slimmed down to nothing more than peeling and drying veneer, with the resulting dry veneer shipped elsewhere.

Un-needed equipment was scrapped or sold, in North America and overseas. Because veneer drying is typically the capacity bottleneck in a mill, dryers often continued to operate within an otherwise idle mill.

Operators figured out how to peel usable veneer from second- and third-growth logs, down to a core diameter of less than 7.5cm. They also found that financial returns could be optimised through selling structurally stronger veneer to LVL producers and then using the left-over veneer for plywood.

Some mill operators identified nonstandard wood species, veneer grades and widths that had value. Typically, this veneer was excess to their needs, or did not fit their downstream equipment or product mix. However, other producers would pay a premium for these non-standard veneers.

Innovation, experimentation and adaptation transformed the Pacific northwest plywood industry. Prudent operators invest profits from good years in efficient technology, debt reduction and other preparations for difficult years. Softwood plywood still plays a major role, but within a larger veneer-based industry.

Disparate environmental impacts

While the invention of OSB equally harmed plywood producers across the Pacific northwest, the impact of heightened societal concerns regarding the environment varied by nation between Canada and the US. Sometimes the reality that responsible forest management is good for the health of the ecosystem – and for the long-term viability of the forest products industry – was lost in the public debate.

Most timber in British Columbia (BC) is harvested from provincially-owned lands. The governments of Canada and BC have always viewed forest products factories as valuable partners for bringing employment and economic development to rural areas: Government policies facilitate the provision of timber to dependable users.

Only in recent years has a natural issue (mountain pine beetle outbreaks after several warm winters) constrained availability.

Most timber in Oregon and Washington grows on lands owned by the US Forest Service, the US Bureau of Land Management, or State agencies.

During recent decades, the relationship between the forest products industry and society regarding the environment – most famously the allegedly endangered Northern Spotted Owl – has been acrimonious. Timber shortages caused by government or court interventions caused log price increases and industry down-sizing. Small private landowners, as well as other non-public lands, have become substantial log sources.

Current industry composition

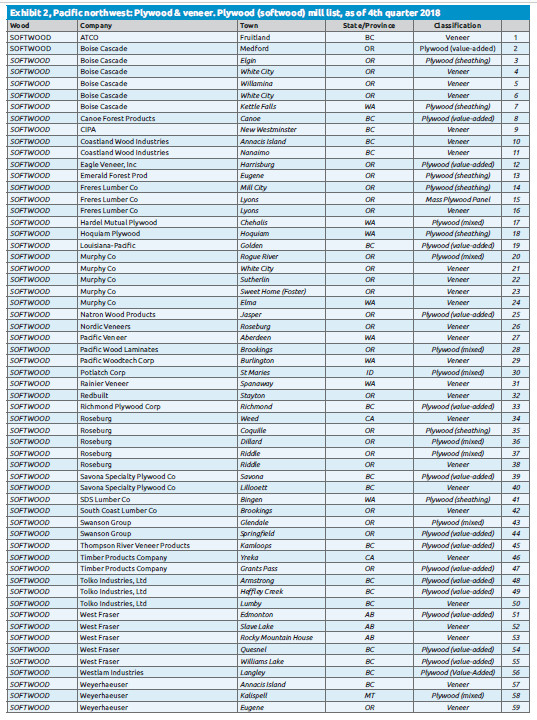

There are 65 operating locations in western North America, comprising 59 softwood veneer-based mills (Exhibit 2) and six hardwood plywood makers (Exhibit 4).

Green and dry veneer production: Thirteen locations, usually adjacent to a significant log source, produce veneer for sister mills, the open market, or both. The two companies described below have recently expanded their operations.

Coastland Wood Industries began as a green veneer producer on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. It later opened a veneer drying plant on Annacis Island, near the city of Vancouver. The company recently installed a state-of-the-art Meinan lathe – its third green veneer line – at the Annacis Island location. The company sells its veneer to plywood, LVL, and Parallam (Parallel Laminated Lumber) producers.

Freres Lumber Company, a family owned business near Salem, Oregon, which has a long-standing reputation for high-quality green veneer, purchased and re-started an idle plywood sheathing plant. The company subsequently installed a satellite veneer drying facility adjacent to its two lathe lines.

Freres is currently developing the Mass Plywood Panel (MPP) concept through a partnership between Freres, researchers at Oregon State University’s College of Forestry, and the new Centre for Advanced Wood Products. Billets of 1.22x2.44m (4x8ft) are laid up at Freres’ plywood plant and then assembled into MPPs of up to 3.66mx14.63mx61cm. MPP is intended for the same uses as Cross Laminated Timber (CLT).

Softwood plywood production

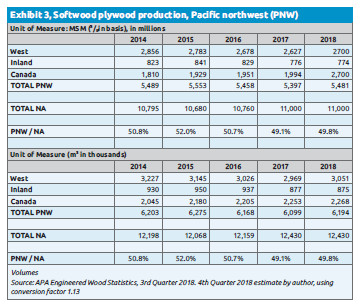

Thirty two Pacific northwest plants produce about half the softwood plywood made in North America.

Only 18 of those are integrated plants, in which a log is transformed into plywood under one roof. The others are so-called layup facilities; most purchase green and/or dry veneer, dry the green veneer inhouse, and sell dry veneer (LVL producers are significant customers) and plywood on the open market. These 32 mills produced about 6.2 million

m3 during 2018 (Exhibit 3). Boise Cascade, West Fraser, and Roseburg Forest Products are the most important regional plywood producers: These three companies operate nine mills, including seven integrated plants.

Boise’s Medford, Oregon, location, the largest plywood plant in North America, has production capacity of over 820,000m3. Only about 60% of veneer is made into plywood, with value-added sanded and concrete form panels as key finished products. The remaining veneer is laid up into semi-finished billets used as raw material by the adjacent LVL plant.

Boise’s two other plants, in Kettle Falls, Washington and Elgin, Oregon are basic sheathing mills with some value-added products.

West Fraser and Roseburg Forest Products largely operate integrated plywood factories, although both have added satellite veneer manufacturing facilities. Both make a high proportion of sheathing, although individual mills also manufacture specific value-added products. Roseburg’s Coquille, Oregon, mill has developed an extraordinary capability to meet customer needs, given that it can reportedly produce up to 660 variations of a 1.22x2.44m panel: Other mills have a narrower product mix.

For example, Pacific Wood Laminates, on the south Oregon coast, manufactures a diverse mix of Medium Density Overlay (MDO) and High Density Overlay (HDO) panels. This mill also produces 1.22x2.44m LVL billets for use in many construction and millwork applications.

Emerald Forest Products produces commodity sheathing in Eugene, Oregon. Green and dry veneer is sourced from a variety of suppliers, including independent veneer producers and other plywood mills.

Emerald can efficiently convert a mixture of widths and species into quality sheathing panels.

Mills have diversified in raw material utilisation, equipment and products sold.

These snapshots represent only a few of the participants in the Pacific northwest region’s plywood and veneer industry.

Producers take advantage of the network of veneer, plywood, LVL, and other veneerbased makers to meet individual mill needs.

Hardwood plywood production

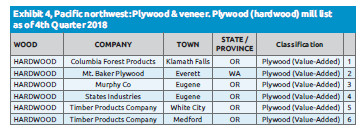

There are six hardwood plywood plants in the region (Exhibit 4), with five in western Oregon.

These mills produce an assortment of appearance-grade panels and components. Most use hardwood outer plies for aesthetic reasons, but have softwood inner plies for reasons such as availability, lighter weight, structural strength and overall stability in service.

Only one hardwood plant – the Columbia Forest Products location in Klamath Falls, Oregon – has a green end. This green end peels whitewoods and other species indigenous to southern Oregon. This company recently acquired a hardwood veneer plant in Ecuador, which peels FSCcertified, fast-growth, plantation timber.

Other veneer based products

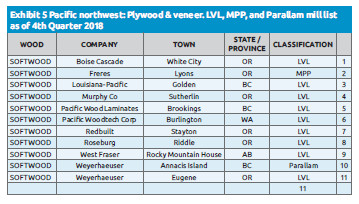

See Exhibit 5. There are three main products which we shall consider here:

- Laminated veneer lumber (LVL): LVL is a parallel lamination of structural softwood veneer, rather than the cross-banding veneer construction that defines plywood. Nine LVL plants in the Pacific northwest consume veneer that would otherwise be utilised in plywood. Notably, LVL production and sales are typically priced via quarterly contracts instead of the auction market of commodity plywood. The result for structural veneer producers is greater price stability; and often a higher price.

- Parallam: Weyerhaeuser operates one Parallam plant on Annacis Island, BC. Dry veneer sheets are chopped into strips, glue and waxes are mixed in, a 73cm-high mat is formed and the mat is then hot-pressed into a 28cm-thick billet. The billet is sawn vertically and/or horizontally to the desired finished dimensions. Timber, beam, and other production is relatively small, at about 13,600m3 per year.

- MPP Panel: The previously-mentioned MPP panel from Freres also currently utilises a comparatively small volume of veneer. That could change over time as the product becomes generally accepted and volumes grow.

The lessons learned

There are three crucial lessons to take away from the plywood industry’s evolution in the Pacific northwest region of North America:

- Firstly, plywood’s core technology of cross-layering fibre to enhance structural properties is still unmatched in strengthfor- weight. Its companion technology, parallel lamination, also has many uses. These veneer lamination technologies can be innovatively used in a variety of additional applications.

- Secondly, the core legacies of resourcefulness and innovation have not been extinguished. This industry mindset will ensure survival and prosperity.

- Lastly, rather than a stand-alone product, plywood has become one component of a vibrant veneer-based industry that is again growing. This industry increasingly seeks to satisfy a broader range of customer needs.

The Pacific northwest plywood industry's experience provides a model as current technologies are challenged around the world and the global industry adapts to meet that challenge.